“Hey hey, ho ho, the patriarchy has got to go,” fifty of us chant as we march past the Eugene Saturday Market. We are protesting the new abortion law passed in Texas along with people in cities throughout the country.

“My body, my choice!” the leader calls out, her voice growing increasingly hoarse. “My body, my choice!” we echo. My voice is extra enthusiastic, responding to the leader's commitment.

“Should you be saying 'your body'?” my partner, a woman, wonders aloud.

“I was talking about circumcision. I don't know what y'all are here chanting about,” I quip. But the wit covers insecurity. Is it improper for me as a man to chant along with women? How do I add my voice as a man in a march that centers women?

Writing this story is my answer. I want to explain why as a man it was so important for me to march for women's rights.

I marched because my liberation is bound up with the freedom of women. Because I have been harmed by patriarchy. Because I longed for love and was shamed instead. Because my numbness, compartmentalization, disconnection and madness is not just personal, it's political.

To become free, we must name what binds us. So, what is patriarchy? It's the system of domination and control of men over women, intimately tied to racism, colonialism, and the destruction of the Earth. bell hooks speaks of “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” The systems of our world have been created by violent men, and violence maintains them.

Robert Levant speaks of seven aspects of patriarchal masculinity:

avoiding femininity

restrictive emotionality

seeking achievement and status

self-reliance

aggression

homophobia

non-relational attitudes towards sexuality

To avoid femininity, with its emotional depth and intuition, is to cut myself off at the neck, to live in a cold rationality without tenderness or sensuality. As a young boy I overheard a conversation between my mom and dad that left lingering doubts about whether it was okay to be the way I was. My dad was worried because I adored stuffed animals. (We threw the best parties.) My mom gently defended my preferences, “It's fine. Just let him be a kid.” But she didn't challenge the premise that I should outgrow them. The doubt lingered: is it wrong to love stuffed animals? Is it wrong to be a tender, sensitive boy?

As young children, we absorb the energy around us. The sensitive nature of my being sensed the collective violence inflicted on my innate feminine qualities. My dad's comment poked a wound more than created it. Perhaps a wound in my soul after lifetimes of trying to transform a violent world.

In the Georgia heat of my childhood we used spray bottles to keep cool during soccer games. One day I discovered that when sprayed on the walls of my room, water beaded in the most beautiful way. I wanted my dad to admire this with me, and to prepare the most beautiful spectacle, I covered my walls with water and ran to get my dad. Upon seeing what I'd done, my dad grew angry. He chastised me like a disobedient dog, grabbed the spray bottle, and left me in my room to reflect on what I'd done. There was no empathy, no shared wonder at the world. His love of the world was primarily intellectual, and when I tried to join him there in my own way, it was somehow wrong.

Patriarchal fathers and husbands enforce their will through shaming, withdrawing, stonewalling, threatening, and inflicting physical violence. When men in our lives are liable to be violent, we cannot share intimacy with trust, love and mutual care. At times, we seek freedom through violence ourselves.

As a boy, I was a fan of Peter Pan. I'd wear green and imagine flying around fighting pirates. While traveling in China as a boy, I bought a dagger the length of my forearm. I felt mature and trusted because my parents allowed me to bring it home. It took on such significance that in my dreams I used it to protect myself against attackers.

One night, when I was maybe 8 years old, I had had enough with my father. I can't remember what he'd done, but a part of me felt I could not live with his power over me. I took the knife and confronted him in the living room.

“Dad, I'm going to kill you.” Desperate, I grasp at violence, or the threat of it, to speak the language my dad might respect.

“Put the knife down, Alex,” his voice powerful and confident.

The dagger drops to the table. My body shakes and sobs. My dad moves closer, concerned and confused. Why is his son so upset?

Without deeper connection to his own emotions, without a culture of honest sharing, without being willing to change, he is unable to understand my challenge, to reflect it back, or to consider ways we could change together. Without further dialogue, I withdraw to my room. Frustrated that I have not found a way out of powerlessness. Ashamed because my murderous impulse is not the loving son I'd like to be, the son I am expected to be.

When there is a way we are supposed to be, we must hide everything else. At times this can help us not enact harm, like murder. But repressing 'bad' impulses reduces our capacity to know ourselves, to feel emotions, and ultimately to transform them. All manner of physical and mental illness stems from repressing emotions. A mask must be constructed: to be good, calm, or powerful. Then when people love us, we fear it is the mask they love and not our true self. If they knew the darkness we hide, we fear we would lose their connection and love. The result of hiding is often powerlessness, depression, and disconnection from ourselves, our purpose, and our aliveness.

Patriarchy robs us of brotherhood as well. Boys intuit the rules and begin to enforce them early on. Words like “fag” are used to dominate others, especially people who don't quite fit the mold. Even people who escape direct attack internalize the rules. I stood silent as a kid on my soccer team, Sam, was called a fag by not just the other boys, but also by the coach. His crime? He was fatter than the rest of us. There was no thought to speak up, to challenge such entrenched power. Flying under the radar seemed safer. I did not want to lose my belonging in the group or the chance to play soccer. Especially when I couldn't always keep up with Sam when we ran sprints.

The ache for acceptance, interest, emotional depth, and love from our fathers and friends is deep and painful. Without avenues for men to grieve, we lose ourselves in work, technology, alcohol, sex, or porn.

But you know this by now. The harms of patriarchy are well documented. Harder is to articulate the alternative. What would the world be like if men embodied:

integrity

loving-kindness

physical affection that honors proper boundaries

capacity to consider and protect people's safety and dignity

emotional awareness of self and other

mutual intimacy, growth, and self-actualization

capacity to be autonomous and connected.

celebration of different explorations and expressions of gender and sexuality

union of love and sex, tenderness and strength

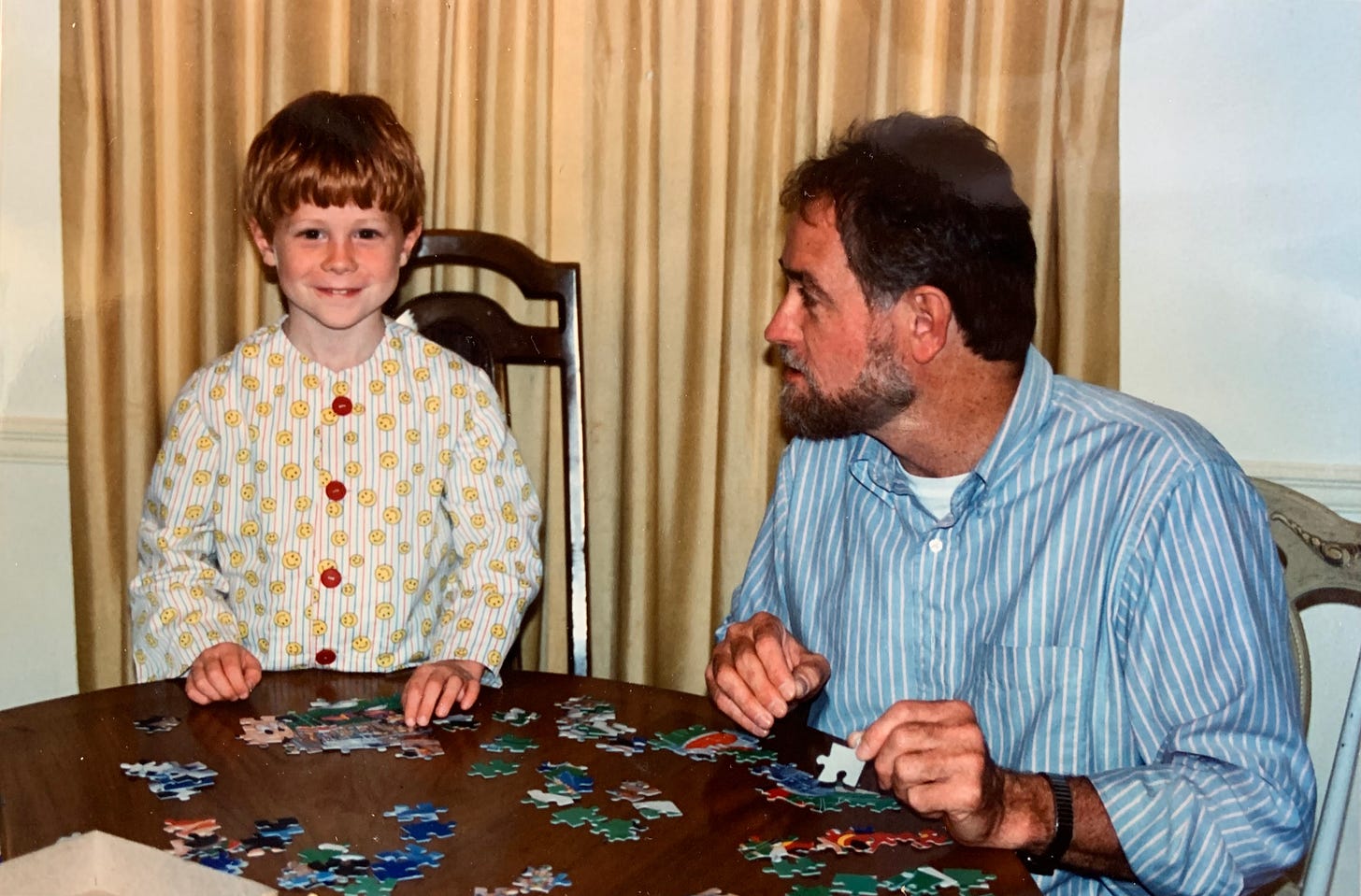

People are not one-dimensional. My father, for example, tucked me in each night. He'd squeeze my arm and sing songs. My favorite was Bob Dylan's dream, with the lyrics changed to include the people most important in my life. Such tenderness and play. We were also best buddies: camping in the Cohutta Wilderness, canoeing the Chattahoochee, and golfing our favorite par-3 course.

My dad is not the enemy. I imagine he has been more emotionally present and kind than his father. I can't be sure because he won't talk about it. Even though my dad lost his patience and resorted to violence at times, he's also human. He has cared for me with generosity and I am grateful.

As we reclaim our power, can we sense the pain of our fathers? Not to justify the status quo, but so we do not become violent ourselves. To maintain our own humanity and dignity. To allow forgiveness and connection. Redemption.

My favorite stuffed animal growing up was Pooh Bear. On time his back ripped open so soft white polyester stuffing spilled out. To me, my best friend had just died.

I slump against the wall, crying for my loss. My dad comes by and gently takes Pooh into his care. With a needle, thread, and the skill of a surgeon, he adds a few sutures and Pooh is saved. My dad: present, concerned, love in action. My tears were welcomed without shame. When men can physically do something, rather than just hold space, many seem more able to help.

When there's an activity, they also seem more able to be present. Remember the soccer team with Sam? My dad loved to watch me play soccer. Often the drives to games were more than an hour, plus 45-minutes of warm ups before kickoff. Sometimes we'd play a tournament that went all weekend. But my dad was in it with me. Yelling as I kicked the ball down field. Sure, tying attention and love to performance encouraged perfectionism. But being witnessed and cheered also built positive self-esteem. He cared.

Recently, when I visited my parents, I had a new kind of experience with my dad. He's older now and his muscles cannot physically contain his emotions anymore. His sweetness at times reminds me of a teddy bear.

We walk into the house co-owned by my parents and uncle to learn that the pump that supplies the house with well water is not working.

“Are you staying here tonight?” my uncle asks. George's finger points at me. He's in emergency response mode. His stress channeled into crisp words and quick movements.

“Yes,” I say nodding my head.

“I want you in the master bedroom.” Where I prefer to stay actually. But I feel unsettled being around strong emotion that is being expressed outwardly without much self-awareness.

George leaves to investigate. I tell my Mom, “I'm going to have to use the bathroom soon. Number two.”

“It's okay. You can add water manually to the tank,” she says.

After I use the toilet, I wonder whether it's better to flush or not. I decide to flush. I turn on the tap in the sink, surprised water comes out, and quickly wash my hands. George is coming up the stairs now. I fear I'm doing something wrong.

Opening the door, George is right there. With intense eyes, he jerks his hand to command me out of the way. His fury is contained in still, silent motions.

As he kneels at the toilet, I close the door to my room and lay down to be tender with myself. The impression of being bad, of an older man's anger, evokes a deep sadness that I cannot quite touch. The consciousness of a young boy arises. I perceive the world as hostile, angry, and unsafe. Where I must withdraw to protect myself.

Mom knocks on the door.

“Alex, will you come out to the porch when you can? Dad and I want to talk to you.”

I walk out, relieved that George sounds far away. We sit on the porch, the green leaves of the trees made gold in sunlight.

“We wonder if you should stay here or come with us [to sleep in another house].” She's in problem solving mode, and I feel disappointed because it misses me emotionally. Noticing perhaps, Mom asks, “How do you feel?”

“Unwelcomed.” The single word echos in our potent field. The ache in my chest, the feeling of being wrong or doing wrong, breaks into tears that flow warm down my cheeks.

“You're welcome here. We welcome you. George does too,” my dad says.

“I could go talk to him with you,” my mom offers.

“And say what?” I ask.

“That you're willing to work with him?”

Not something I'm up for at the moment. I shake my head no. Though I appreciate the intent and attention, I wish she'd stop problem solving and just be with me.

In the silence, I start to sob.

My dad immediately stands, a bit wobbly, and holds out his arms. I stand up and gladly receive his hug. My mom slides in behind. There, in the embrace of my parents, I feel the depth of pain and in a breath, I feel warmth flooding my chest. Joy and space where there was aching despair. Sweet relief. With the willingness to be vulnerable and the willingness to allow vulnerability, the imprint of a hostile world transforms.

Back in my room, alone, I ask my grandparents to help me see their son with their eyes, with love. I don't know his inner story. It's hidden, like my fathers, behind walls of silence. How can we understand when we cannot see the pain beneath anger? Feeling connected to the love of my grandparents, the energetic conflict with my uncle dissipates. I don't know how much emotional connection is available with him, but there is at least a baseline of openness and respect.

I wonder too, about what led me to use the water in the first place. Faintly, I can feel an urge to test the limits of acceptability: will I be loved even when I make this mistake? Maybe there was a longing to be triggered and to heal. A house without water, like a human without grief, cannot release its shit.

A bit later I talk to my uncle. “I'm sorry for flushing earlier.”

“It was just awkward timing.” Uncle George is calmer now. “You know you don't have to stay in that room all day.”

Maybe that was his way to invite me in, to welcome me. “You don't have to stay in that room all day.”

What my family modeled is the beginning of what the world without patriarchy looks like: holding each other when life gets painful. A world where men can grieve for what we have wrought.

Collectively we are at a time of reckoning with our past of using power-over. The Earth will have it no more, and her people are calling out from depression and despair for a new way forward. To feel our way back to remembering our divine wholeness, I ask you four profound questions. Questions, according to anthropologist Angeles Arrien, that indigenous healers use to heal disease:

When did you stop dancing?

When did you stop singing?

When did you stop being enchanted by the story of your life?

When did you stop being comforted by the sweet territory of silence?

If you know when your spontaneous physical and emotional expression was blocked, and you feel the impact that moment had on you, you can reclaim your body, voice, and self-esteem. We must hold, in silence and in song, our pain and let it lead us to our inherent strength. Revealing our resilience, the path through trauma hones our humility, cultivates our compassion, and teaches us to live with respect and gratitude for all life.

AWESOME !!!! Great article ALEX. Thanks for sharing your personal stories regarding some of the ways "the patriarchy" has effected you.

This is a beautiful expression of your heart, and the use of your own story to look at the complex story of patriarchy. I teared up a couple of times. Having been in that house, having used that toilet, having met your uncle, and both your parents, it moved me. Some deep stirrings. I made a dipping sauce with butter yesterday, and it kept separating, and settling at the bottom, needing to be stirred. Your story has stirred my own, and my own ponderings, and I feel less lonely in them. Thank you for sharing this. I feel it could be beneficial for others. Love you, sweet friend.